Myth: There Were 13 Colonies

Truth: Like the rest of us, you probably bought the ol’ Thirteen Colonies story, but it’s not an accurate depiction of colonial America for most of its history. As settlements were founded, each new city was recognized as its own colony: for example, Connecticut contained 500 distinct “colonies” before they were merged into one in 1661. Sometimes colonies were mashed together into mega-colonies, like the short-lived, super-unpopular Dominion of New England, which incorporated Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Connecticut, New Hampshire and Maine, plus New York and New Jersey for a couple of years. Colonies also split, like Massachusetts, which spawned New Hampshire in 1679. And some colonies weren’t colonies at all: while it’s often listed as one of the Thirteen Colonies that rebelled in 1775, Delaware wasn’t technically a colony or a province. Designated “the Lower Counties on the Delaware,” it had its own assembly but fell under the authority of the governor of Pennsylvania until it declared itself an independent state in August 1776. So technically, there were just 12 colonies in 1775 and 13 states in 1776.

Myth: Social progress began in cities and then filtered out to rural areas.

Truth: Sorry, city slickers! While women’s suffrage was discussed everywhere in the United States in the nineteenth century — most notably at the Seneca Falls Convention organized by Elizabeth Cady Stanton in upstate New York in 1848 — the first real progress came on the Western frontier.

In 1869 the Wyoming territory became the first political entity in the Northern Hemisphere to grant women the right to vote regardless of their professional or marital status. It also passed laws allowing women to hold public office, own property and elected the country’s first female judge. So why was Wyoming so far ahead of the curve? The biggest reason is that men in Wyoming appreciated their women. After all, there weren’t many of them—in 1870, there was just one woman for every five men in the territory. Life was tough on the frontier, between the sod houses, blizzards, outlaws and small pox, and the women in Wyoming often worked alongside the men, hunting, farming, ranching, and prospecting for gold. Legislators hoped that by giving women rights, it would lead more women to move there. Indeed, women’s suffrage spread quickly in places where women were scarce; Colorado, Utah, Idaho, Washington, California, Arizona, Oregon, Kansas, Alaska, and Montana all granted women the right to vote by 1914. When it came to women’s suffrage, it was the city folks back East who needed to catch up.

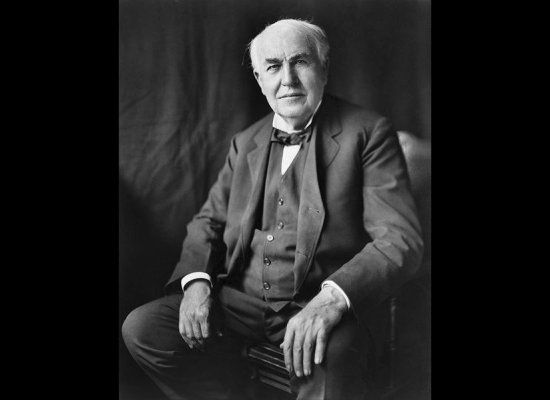

Myth: Thomas Edison got his start in science because he came from a wealthy, educated family.

Truth: If the 15-year old Edison hadn’t saved a boy from a runaway train, his life could have turned out pretty differently.

To understand why Thomas Edison is such a nerd hero, all you have to do is skim his patents. The man invented the lightbulb, the phonograph, electric railroads, underwater search lights, a trick for camouflaging navy ships, and over a thousand other important things. But none of that would have happened, if Thomas Edison hadn’t saved a child’s life first.

In 1862, at the age of 15, Thomas Edison got his first job as a newspaper boy at a train station in Mount Clemens, Michigan. One day, while hawking papers, Edison noticed that a three-year old boy was playing on the tracks, right in the path of a runaway freight car. Although the engineer had spotted the boy, and was trying desperately to stop the car, he couldn’t. The quick-thinking Edison jumped on the track, swooped the boy up in the nick of time, and then dove away from the speeding train.

The action not only saved the boy’s life, but it changed Edison’s as well. The boy’s father happened to be the station’s telegraph operator. He was so grateful to Edison that he took him under his wing, and trained him in telegraphy, sparking the inventor’s lifelong love affair with all things electric.

Myth: Columbus realized he’d discovered a new land.

Truth: The bullheaded Columbus believed till the end that he’d landed in Asia.

Back when he set out to sail the ocean blue, Christopher Columbus drastically miscalculated the circumference of the earth at 19,000 miles vs. 24,900 miles. That’s because he based his projections on Roman miles (4,840 feet) instead of nautical ones (6,080 feet). Whoops!

So when the explorer’s ships landed at the Bahamas in 1492, Columbus assumed it was Asia. He saw no sign of the spices he sought, but he did find some people to call “Indians” and he proceeded to steal their gold. In 1493, Ferdinand and Isabella sent Columbus back with instructions to rob the place blind.

This is where an understandable mistake turns into obstinate stupidity. On the four return expeditions, everyone but Columbus realized the land they were exploring wasn’t the East Indies. Some of the evidence to support this included the natives’ repeated testimony that they’d never heard of China, Japan, India, silk, pepper, elephants, or any of that nonsense.

Amerigo Vespucci, dispatched as quality control in 1499, wrote that “these regions . . . may rightly be called a new world,” and later had his name stamped on the place. But Columbus scoffed at his colleague, dismissing the locals as “bestial men who believe the whole world is an island,” and forcing his crew to sign an affidavit declaring they’d discovered Asia. Columbus died in 1506, still believing he was right.

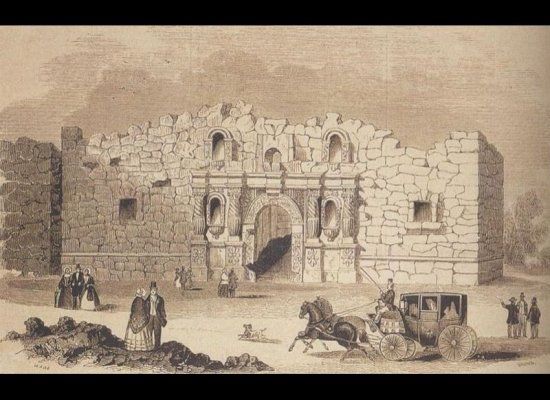

Myth: The Alamo was about defending liberty and freedom.

Myth: The Alamo was about defending liberty and freedom.

Truth: The roughly 250 Americans who died at the Alamo weren’t defending liberty— they were protecting slavery.

Texas was still part of Mexico after its War of Independence from Spain. But the land attracted so many American settlers, that they soon outnumbered the Mexicans. Incredibly, that was just fine with the Mexican government. In fact, many Texans wanted Texas to become a Mexican state.

But trouble started brewing in 1829, when slavery was banned throughout Mexico. This angered settlers who moved to Texas specifically to establish Southern-style, slave-powered plantations. Texas was briefly given an exemption, but in 1835, General Santa Anna revoked it.

Enter the Alamo. Overconfident after a few easy victories against smaller Mexican forces, the Texans divided their army and left just a few hundred men in San Antonio. Santa Anna surprised the town in February 1836, causing 250 rebels to take refuge in the Alamo under the informal leadership of Davy Crockett and James Bowie.

There was no way the rebels could break the siege— it was 1,500 Mexican troops to their 250— but there was no point in surrender either: Santa Anna had announced that he would take no prisoners. In the end the defenders were all killed.

Against all odds, Santa Anna’s cavalry was later defeated in just 18 minutes by a smaller force of Texans in a desperate surprise attack. They captured Santa Anna as he tried to flee through a nearby swamp. The humiliated dictator ended up trading Texas for his freedom and the Texans succeeded in upholding slavery. For the next nine years, the Republic of Texas existed as a nation unto itself, before joining the United States in 1845— needless to say, as a slave state.

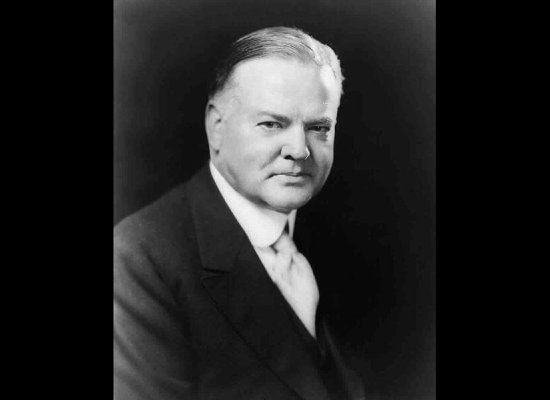

Myth: Herbert Hoover didn’t do anything to counteract the Great Depression (and FDR saved the day with The New Deal).

Myth: Herbert Hoover didn’t do anything to counteract the Great Depression (and FDR saved the day with The New Deal).

Truth: Hoover tried many things, but sadly, America might have been better off if he hadn’t. But was the new guy— Franklin Delano Roosevelt -- really all that different? The truth is, most of FDR’s initiatives were simply continuations (or expansions) of Hoover-era policies.

The only real difference was FDR’s willingness to distribute relief aid directly to ordinary Americans, which alleviated suffering but did little to end the downturn. Aside from this, their supposed differences are mostly the product of PR spun by both sides during the 1932 election.

So why did a strategy that failed for Hoover work for FDR? Easy: it didn’t. In fact, the series of social and economic reforms enacted by FDR (collectively known as the New Deal) delayed recovery by allowing big business to form anti-competitive cartels, raising the price of consumer goods, discouraging hiring by decreeing high wages, propping up failing businesses, and crowding out private investment. What really revived the American economy? War.

Myth: Baseball is distinctly American.

Myth: Baseball is distinctly American.

Truth: Baseball was probably derived from “Rounders,” a game played in Ireland since the fifteenth century.

By the eighteenth century, rounders incorporated many of the basic elements of modern baseball: two opposing teams with one in the field and one batting; successive batters trying to hit a small ball and then make the “round” of four bases to score. Three strikes and you’re out!

During the 1820s-1850s, Irish immigrants brought rounders with them to the New World, where local variations developed. In the Massachusetts variant, the batter stood between home plate and first base, and the opposing team could “out” someone by beaning them with the ball. Runners weren’t required to stay on the baselines, meaning there was an element of “tag.” The Philadelphia game gave us the familiar diamond-shaped field and nine players to a team.

In 1845 it was decided to standardize the rules of New York’s game. The Knickerbocker Rules decreed nine innings and said any “knock” outside the lines of first and third base was foul. In 1858 they added the “strike zone,” and in 1863 they added the automatic “walk” after four balls.

For a while, the Knickerbocker Rules also required underhand pitching. Of course, the biggest surprise might be that until 1865, Knickerbocker Rules also allowed fielders to out the batter by catching the ball after one bounce. This was mostly for safety purposes since the game was still played without gloves or protective gear.

Myth: John Wilkes Booth helped the South by assassinating Abraham Lincoln.

Truth: Just the opposite. He succeeded in making things (much) worse for his beloved South.

Lincoln had always advocated a lenient policy for the Reconstruction of the South: he wanted to have all the Confederate states reincorporated into the Union by the end of 1865 and proposed relatively moderate requirements for readmission. Vice President Andrew Johnson was ready to carry out Lincoln’s moderate plan— but after the assassination, he didn’t have the authority or charisma to control Radical Republicans in Congress who took a much harsher approach, motivated in part by anger over Lincoln’s assassination. In the end, Booth’s last act only made a bad situation worse for his beloved region.

Myth: America defeated Nazi Germany with help from its plucky British sidekick.

Truth: The Soviet Union defeated Hitler pretty much by itself.

While American and British participation did help shorten the war considerably, by the time the U.S. joined the effort, the Soviet Union had already done most of the work.

From the Nazi invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941 to the end of the war, the number of German troops deployed on the Eastern front never sank below three-quarters of Germany’s total strength. As a result, the Eastern front saw mind-boggling casualties: just under 90 percent (3.2 million) of German combat deaths and three-quarters of German tank losses occurred there. On the Soviet side, 11 million soldiers died, including 2 million in German POW camps. Combined with civilian deaths, the total Soviet toll came to an astonishing and horrifying 25 million, compared to 1.3 million combined military and civilian deaths for the United States, U.K., and France.

The truth is, the U.S. and U.K. weren’t eager to jump in. Stalin mentioned opening a second front in Western Europe in July 1941, and in June of 1942 the Western Allies assured him the invasion of France would begin no later than September 1943. When it didn’t, Stalin withdrew his United States and U.K. ambassadors, accusing the Western Allies of delaying so the Germans and Soviets could wear each other out. And he may have been right.

The U.S. did help the Soviet Union with supplies, including tanks, planes, and locomotives, but this aid only accounted for about 9 percent of Soviet war time needs. The British and Americans also “helped out” by dropping about two million tons of TNT and napalm on Germany, killing over 300,000 civilians, but “strategic bombing” achieved little: important German factories moved underground, and war production actually increased from 1942 to 1944.

Myth: Old people supported war in Vietnam, while young people opposed it.

Truth: It turns out younger Americans (under the age of 30) were consistently more likely to support the war in Vietnam than those over the age of 49, with middle- aged folks falling somewhere in, well, the middle. In August of 1965, a Gallup poll found 76 percent of adults under 30 supported U.S. intervention in Vietnam, versus 51 percent of adults over 49. By July 1967, those numbers had changed: 62 percent of the under- 30 crowd still supported intervention, while the over- 49 crowd was down to 37 percent. In January of 1970 those numbers fell to 41 percent and 20 percent, respectively.

What explains those trends? It’s anybody’s guess, but it may be due to the older generation’s personal experience of conflict in World War II and Korea— including shortages, long separations, and the loss of loved ones— which made them more cautious about rushing into new fights... especially if they had sons eligible for the draft.

Myth: The stock market crash on October 24, 1929, caused the Great Depression.

Truth:The economic downturn was already under way on that infamous date in history, thanks to credit-happy consumers and reckless lending.

The Federal Reserve Banks controlled the money supply by adjusting the interest rate on loans to private banks. Not really understanding the impact of what they were doing, officials kept interest rates low through the 1920s because it was politically popular. The loans allowed businesses to invest in new factories and consumers to buy more stuff. When American exports were too expensive for foreign consumers, the U.S. government simply boosted foreign demand by encouraging American banks to lend the foreigners billions. The whole system was pumping more air into a credit bubble now engulfing the world.

With easy credit access, more consumers bought more goods at higher prices, allowing businesses to hire more employees at higher wages. This gave them collateral to borrow more money and buy more stuff, which . . . you get the idea. Easy credit also led to rampant stock market speculation, with stockbrokers lending investors up to 90 percent of the value of the stocks they’d bought. This wasn’t good for that growing bubble.

The merry-go-round had to stop eventually. When the Federal Reserve finally pulled the plug in 1929, raising rates after a belated change of heart, the wild ride immediately ground to a halt. U.S. industrial production stalled in June 1929. By September, the standstill triggered big slides in stock prices, and October brought panic. Stockbrokers called in loans, speculators started going bankrupt, and many investors were ruined. Then the market recovered: after tumbling from 380 in mid-October to below 200 in November, by April of 1930 the Dow was back above 290.

So if the U.S. survived the infamous Black Friday crash, what actually kicked off the Great Depression? The truth is, there was another crash— the “real” crash— with the Dow Jones plunging from 270+ in June, 1930 to 41.22 on July 8, 1932. Spread out over two years, this 85 percent decline was less of a crash and more of a slow, groaning collapse.

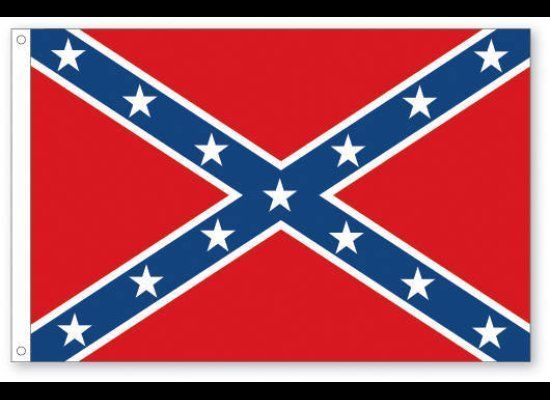

Myth: During the American Civil War, the South was unified in wanting to secede.

Truth: There was widespread opposition to secession in certain areas – especially the “Upland” South. One part of Alabama even declared independence because it refused to align itself with the Dixie!

Unlike plantation owners in the Deep South, the whites in Appalachia – largely the descendants of Scots-Irish settlers –had no financial stake in slavery and tended to be more ambivalent. While the wealthier members of the community, who might have owned a handful of slaves, were usually staunch supporters of the Confederacy, most of the poor “dirt farmers” saw no reason to fight for the right of the wealthy to own slaves. These feelings essentially mirrored the sentiments of poor whites in the North, who saw no reason to fight to free the slaves.

In the end, the Midlands were effectively a third force in the Civil War, which tried (and failed) to steer a course between the Union and the Confederacy. Kentucky and Missouri declared their neutrality before being invaded by both Confederate and Union forces in 1861. Meanwhile, counties in northern Alabama and eastern Tennessee tried to secede from the Confederacy and rejoin the Union. Incredibly, some groups succeeded: West Virginia seceded from Virginia to form a new Union state in 1863, and the citizens of Winston County, Alabama, declared themselves the Republic of Winston and defied Confederate authority to the end of the Civil War, helping Union forces with local scouts.

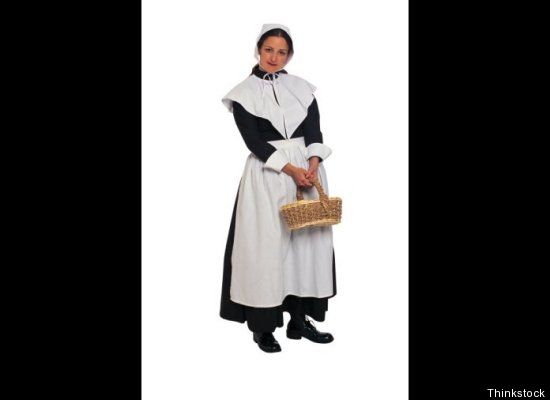

Myth: The Puritans came to America to establish religious freedom.

Truth: The Puritans came to America to escape other people’s religious freedom.

In 1593, radical Protestant “Separatists” emigrated from England to Holland to live in peace without being hung or jailed for religious nonconformity. That led to a new problem for the Puritans: the Dutch allowed people to practice all sorts of “crazy religions,” including Judaism, Catholicism, and even atheism. Worried about their children’s morals, the Separatists hopped on the Mayflower in 1620. Remembered as “the Pilgrims,” they wound up in what is now Massachusetts and founded the first Puritan colony in the New World. Although half of them died the first winter, Separatists were so eager to get away from Holland and England that two more boatloads arrived in 1623 and 1627.

Inspired by the so-called success at Plymouth, about 20,000 non-Separatist Puritans left England for Boston. But these non-Separatists proved just as intolerant. When Roger Williams suggested detaching church from state, he was banished and went on to found Rhode Island. Fellow rebel Thomas Hooker led his more relaxed followers to Connecticut. Shortly thereafter, Puritan elders exiled a woman for criticizing their authority, like Puritans had criticized the Catholic and Anglican clergy. It seems that Puritans, in addition to disapproving of laughing, smiling, dancing, and touching, did not have a sense of irony.

The bigger point is that seeking isolation across the ocean didn’t solve any of their problems. The Puritans were surprised when new immigrants and their own children didn’t share their religious ideals. In 1691, King Charles II accelerated the Puritan society breakdown when he changed the colony’s royal charter so that property ownership became the basis of voting rights instead of membership in a Puritan church. He also amended the charter to include protection of religious dissenters. Looking back, the old-fashioned Puritans might have regretted the move overseas.

No comments:

Post a Comment